The 350th solar return of the placing of the foundation stone of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich was on August 20. Woo-hoo, right? No?

Well, it was an important milestone in the history of astronomy, as the Royal Observatory went on to help establish England as a world-class center for science, supplying accurate ephemerides for Isaac Newton, who definitely wasn’t an alchemist, and, I guess, members of the Royal Society, who were definitely not astrologers, wink-wink, nudge-nudge.

One notable thing about the event concerns an astrological chart, crafted by the first Royal Astronomer, John Flamsteed, showing the moment of the foundation stone’s placement. The chart was kept inside the inner sanctum for over a century, until it was finally noticed, and then published, in the 1800s. The following excerpt is taken from The Every-Day Book (a popular UK history book of what important stuff happened on which dates), which shows us a rendering of the chart:

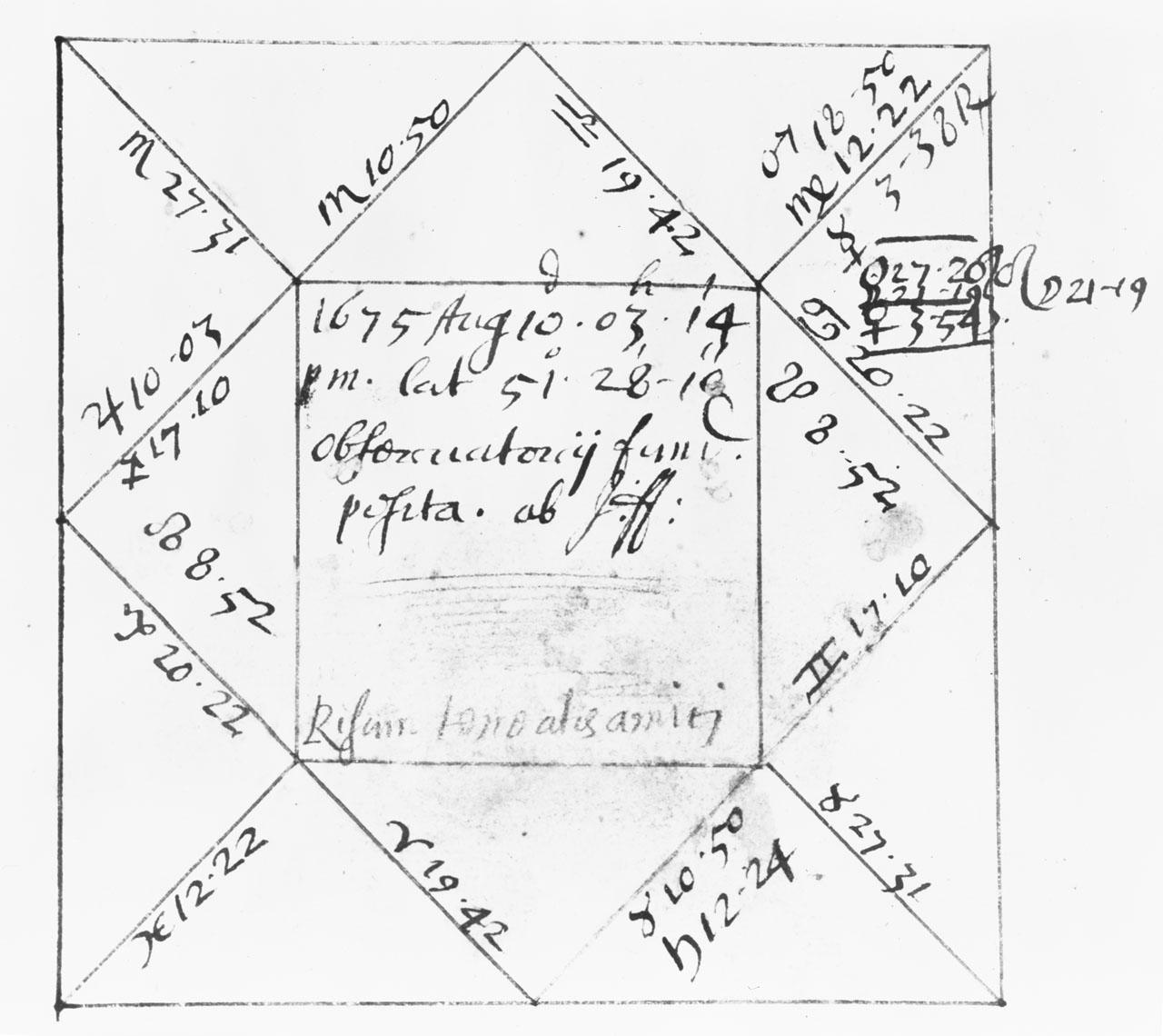

An actual scan of the original chart cast by Flamsteed is here:

The chart lists these posits:

Ascendant @ 17°10′ Sagittarius,

Midheaven @ 19°42′ Libra,

Sun @ 27°26′ Leo,

Moon @ 21°19′ Leo,

Mercury @ 3°38′ Virgo,

Venus @ 3°54′ Leo,

Mars @ 18°50′ Virgo,

Jupiter @ 10°03′ Sagittarius,

Saturn @ 12°24′ Taurus,

North Lunar Node @ 8°52′ Capricorn.

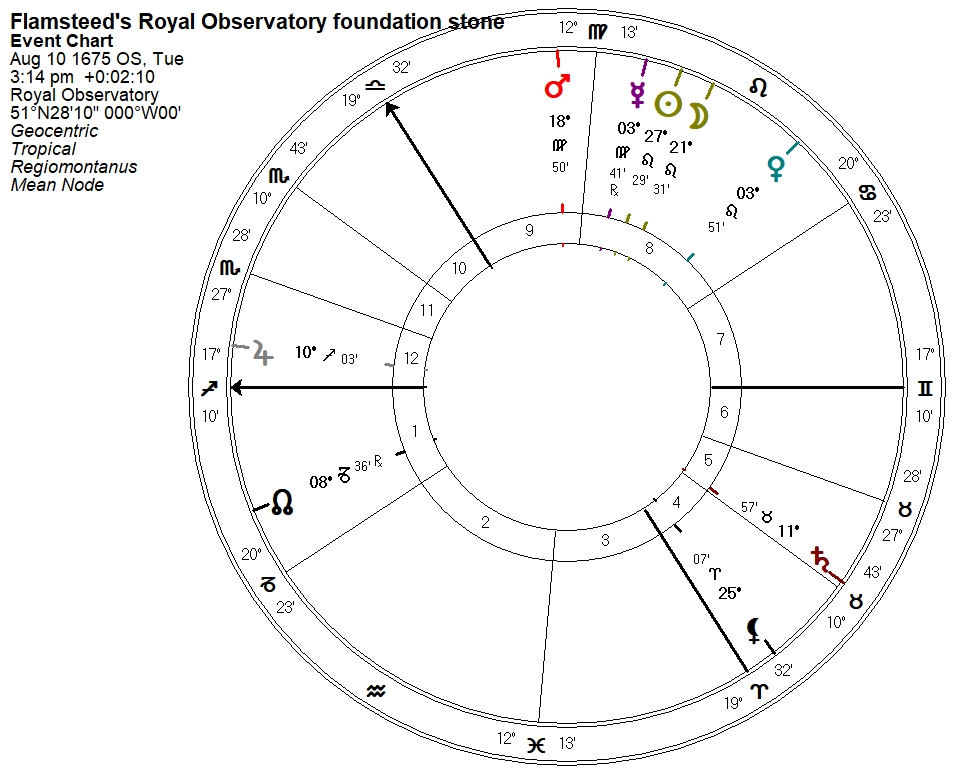

A modern chart in Solar Fire with the same ascendant looks like this:

A persnickety viewer of the Solar Fire chart will want to know why the time adjustment is 2 minutes and 10 seconds instead of zero, and that’s because Flamsteed was using the Paris Meridian, which was the standard of the day. The Greenwich Meridian had yet to be established by, well, by Flamsteed and the Crown through the Royal Society.

And, we can see that the values for the planets are all deviant to some extent, with the notable exception of Mars. The midheaven is also 10′ of arc different, but, hey, no big deal, this isn’t rocket science.

So, the question remains to this day: why did the prominent astronomer craft such a chart? One would suspect that this was in line with how things were done back in those days, as England was at the tail end pf the golden age of Almanacs and astrological interest. I noticed Nick Campion musing about this on a astronomy discussion group earlier this year, saying of Flamsteed’s chart:

The horoscope is indeed a very fortunate one according to the rules set out in William Ramesey’s ‘Astrologia Restaurata’ of 1653. Surely, if Flamsteed wanted to mock astrology he would have created a spoof horoscope.

Flamsteed is also known to have cast the horoscope for the inauguration of the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich (5 pm, 30 June, 1694), nineteen years after the Greenwich observatory foundation, which points to a long-term commitment.

The overall evidence suggests that Flamsteed followed in the reforming lineage of which Kepler was a part, accepting the principle of astrology but criticising both the practitioners and many of the practices.

May I refer HASTRO members to pp. 164-5 of Vol 2 of my History of Western Astrology. – Nick Campion

Aside from Campion, the prevailing notion among historians downplays any kind of thaumaturgy, but insists that Flamsteed was being flippant and sarcastic. The main reason for that notion is the note at the bottom of the inset: Risum teneatis amiti. Whomever transcribed the chart for Hone’s Every-Day Book had apparently mis-transcribed the Latin:

What does this little quip mean? Some basic translations suggest a cheerful, if not jocular tone:

Risum teneatis, amiti = Keep smiling, my friends.

Risum tene atigamite = Hold your laughter, please.

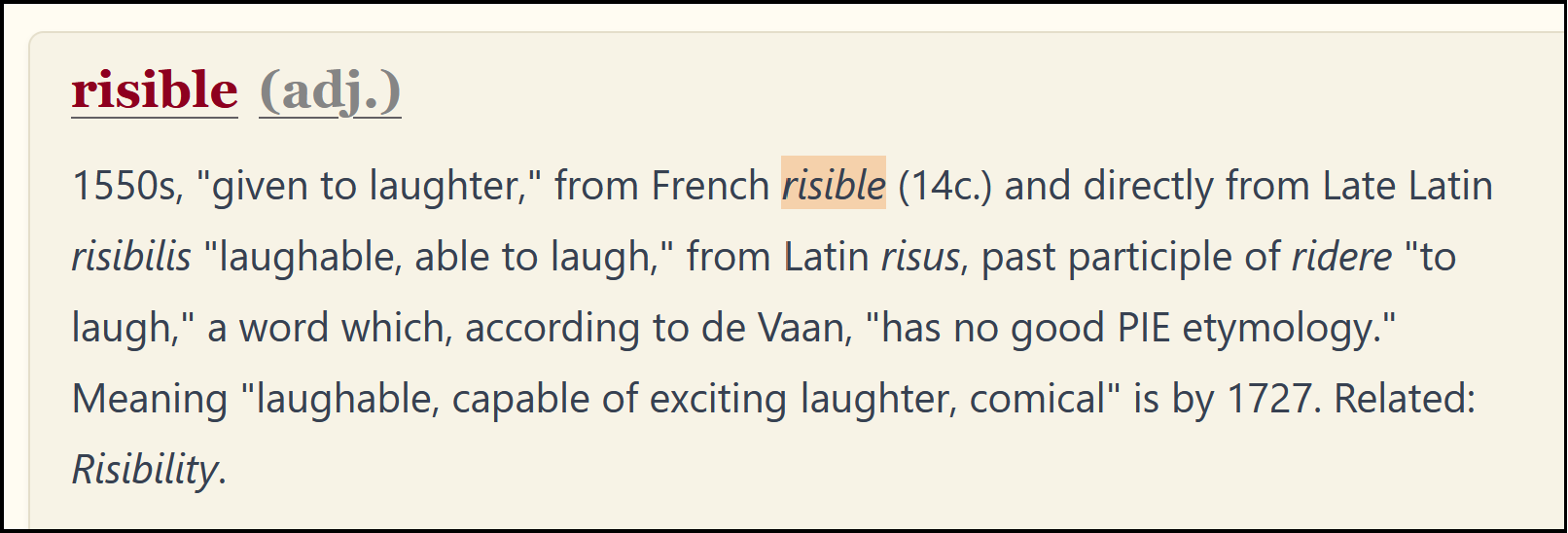

The Risum is from the Latin root meaning to laugh:

The meaning of “risible” in English has always been simply about having a laugh:

Having a laugh can also come at the expense of someone else. The idiom about “getting a rise” out of someone comes from that erudite tradition of belittling the captive neophyte student::

Indeed, the rascal scholar is always up for some high-brow laughs. Academia loves its shenanigans and inside jokes.

Was Flamsteed trying to somehow ridicule the very Royal Society that hired him? Or, was he making a more subtle joke for his compatriots that only they could be in on? Rebekah Higgitt’s history of science blog tells us that the Latin phrase comes from antiquity:

… this horoscope remains intriguing, for a number of reasons. Firstly, it includes the Latin motto “Risum teneatis amici”, taken from Horace and usually translated as “could you, my friends, refrain from laughing?”. Was this meant sarcastically, or defensively?

https://teleskopos.wordpress.com/2011/08/10/an-auspicious-day-to-found-an-observatory/

Horace, you say? The masterful poet who lived in the 1st Century BC and was often up for some good humor? Where would we find him using this? In his De Arte Poetica, or “The Art of Poetry.” To wit:

Humano capiti cervicem pictor equinam iungere si velit,

et varias inducere plumas undique collatis membris,

ut turpiter atrum desinat in piscem mulier formosa superne,

spectatum admissi risum teneatis, amici?

———————————————–

If a painter wishes to join a horse’s neck to a human head,

and to introduce various feathers on all sides,

so that the beautiful woman ends shamefully black in a fish,

will you hold back your laughter, friends, having admitted the sight?

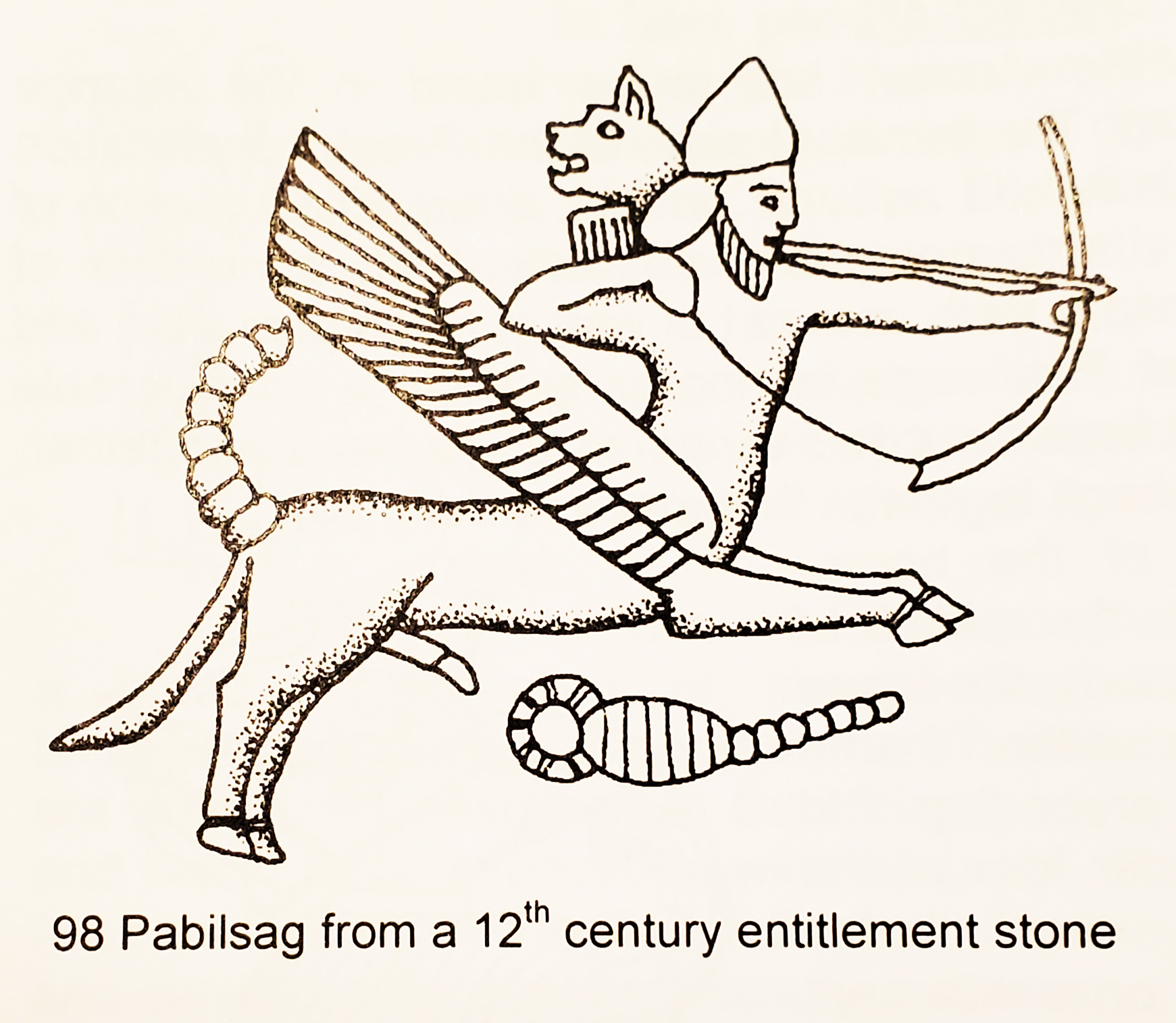

A human head, on the neck of a horse? With feathers? Where in the cosmos might such a silly creature be found?

That’s right, the constellational iconography of Sagittarius, which combined a horse, a human head, and some wings:

And which has survived to this day as the motif of the astrological “sign” of The Archer, though the wings are mostly missing:

Slap the head of panther on the caricature, and we go all the way back to the most ancient of times…

Getting back to the foundation stone chart, we find that Sagittarius is the ascending sign – the RISING sign. Rising/Risum. Get it?

But it doesn’t end there. The Royal Society that hired Flamsteed began some years earlier, in 1660, when Christopher Wren, the famed mathematician and architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral, organized a lecture at Gresham College and invited many bright minds to attend. After the lecture, a core group of scholars conferred, and formed what would be called the Royal Society, after convincing the Crown to give them title and money. That lecture happened on November 28, and the Sun on that day was in the sign of … you guessed it … Sagittarius.

In fact, the Sun was in the 18th degree of Sagittarius, conjunct the ascendant of the Flamsteed chart, as this bi-wheel reveals:

Flamsteed sure packed a lot of punnery in pudding. That, my friends, was pretty fucking hilarious in the 17th Century.

But, wait, is there even more? As it happens, if we put an outer ring of Behenian fixed stars on the chart, we find that the midheaven is exactly on both Spica and Arcturus – the only stars that are “conjunct” from the ecliptic point-of-view:

Adding to the chuckles, the Sun is widely conjunct Regulus, but the Lunar Nodes are aligned with Sirius while Capella is on the descendant. Are your sides splitting yet?

Did Flamsteed actually direct the Royal Observatory’s builders to place that foundation stone when Spica and Arcturus were culminant, as Campion suggests? We do know Flamsteed was well-versed with crafting astrology charts, which he learned to do in his formative years when he was cloistered due to illness.

Did Flamsteed “believe” in astrology? Not in the sense of a typical horoscopic astrologer of our era, but the point of erecting charts in the first place is to become familiar with where things are in the heavens and how it all works.

His obsession with accuracy of celestial measurement brought him in contact with the right people in the Royal Society, and in the end he got to do what he really loved. He gave England’s professors the most accurate ephemerides possible, which aided the work of Isaac Newton, for instance. It also aided the colonial nation-builders like Benjamin Franklin, for instance, who was no slouch when it came to astronomical charting.

As I often say, the late 17th Century and early 18th Century still had one foot in the supernatural aether and the other on the materialistic ground of scientific pursuits. It was still a time of transition out of the Renaissance and into the Enlightenment, and like all of us, Flamsteed was a captive of his own time. My contention is that he elected his chart not only to take advantage of a fortunate astrological moment, but also to tap into the extant astro-scenario of the Royal Society itself.

The Royal Observatory was all about the heavens, after all, and even the slightest superstition could still haunt the mind that needs both heaven and earth to be properly aligned to honor God and his creation.

All jokes aside, if my take on this is accurate, what Flamsteed pulled off was … I’m just gonna say it … SAG-acious!

►Ed

Header photo credit: https://www.worldhistory.org/image/18037/the-royal-observatory-greenwich/

Leave a comment